Land supply in Beijing had fallen for six straight years before April’s new rules were issued

As China’s real estate market spiked in 2016, dozens of Chinese cities followed central government directives and announced local measures to tackle rapidly rising home prices.

These local tightening moves primarily came in the form of controls designed to reduce demand for housing, including raising mortgage rates, boosting down payment requirements, and restricting eligibility for home purchases to local residents.

Yet while these demand-side restrictions had been effective in previous rounds of market tightening, average home prices in China’s first tier cities rose 23.5 percent in 2016, with average prices also rising 14 percent and 11 percent in second and third tier cities respectively, according to data from real estate information provider China Index Academy.

Top Ministries Takes Over After Cities Fail to Tame Prices

As average housing prices continued to rise in the first three months of 2017, the government effectively accepted the failure of last year’s demand side initiatives by local regulators.

Then on April 1st China’s Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, together with the Ministry of Land and Resources, jointly announced new rules governing land sales “to strengthen the adjustment and control of housing and land supply management in the near future.” The official People’s Daily characterised these new measures as evidence of the central government’s resolve to solve housing market problems from the supply side.

Tying Land Sales to Housing Supply

MOHURD chief Chen Zhanggao announced the new rules on April 1st

Under the new regulations, local governments are required to create land supply plans for the next three and five years, and to publish these development blueprints.

Specifically, the new rules dictate that, for cities with an overhang of existing housing stock equivalent to 36 months or more of recent monthly sales, auctions of new land should be stopped. Communities where existing housing supply is equal to 18 to 36 months of sales are instructed to reduce the supply of new land put on the market.

Meanwhile, cities whose unsold housing is equal to six to 12 months of supply, are now supposed to increase land sales, and communities with under six months of supply are expected to begin selling more sites in a timely manner.

Given the lack of eager buyers for sites in cities with an oversupply of homes – usually in third and fourth tier cities – the central government’s directives to decrease land supply in those communities should be easily implemented. However, the practical and regulatory realities of increasing land sales in China’s first tier cities, and larger second tier cities, can be challenging for a variety of reasons.

New Rules Collide with Old Guidelines

For local governments that are attempting to follow the new rules, there are conflicts with existing plans agreed with the central authorities, especially in the case of China’s fast-growing megacities, such as Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen.

Under the existing system, each city is required to preserve a minimum amount of farmland, which limits the amount of land made available for development. Within the municipal development plan, the quantity of residential land supply is based on predictions of population levels.

In Shenzhen, for example, city planning is driven by the Overall Plan on Land Use drafted in 2008. The nearly decade-old plan predicted a city population of 9.5 million in 2010, with that number rising to 11 million by 2020. However, despite the plan still being in force in 2017, Shenzhen’s population had reached 10.4 million in 2010 and stood at 11.4 million in 2016.

As Chinese people continue to flow towards the economic opportunities presented by the country’s largest communities, Beijing, Shanghai and other mainland megacities also suffer from similar conflicts between out of date plans and rapidly rising populations. The result is insufficient land supply.

Urban Needs and Government Goals

While there are options for local governments to increase land supply, these often run up against central government goals of restricting population growth in first tier cities, boosting the efficiency of land use, protecting the environment and avoiding mass incidents triggered by land expropriation.

With these central government concerns driving top level policy, over the last six years, the amount of new land put up for sale each year in China’s largest cities has been decreasing steadily. This is happening at the same time that housing prices in these urban hubs has been heading upwards each year.

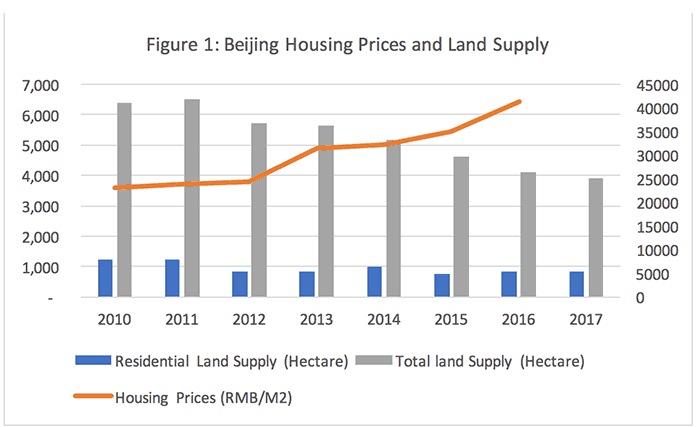

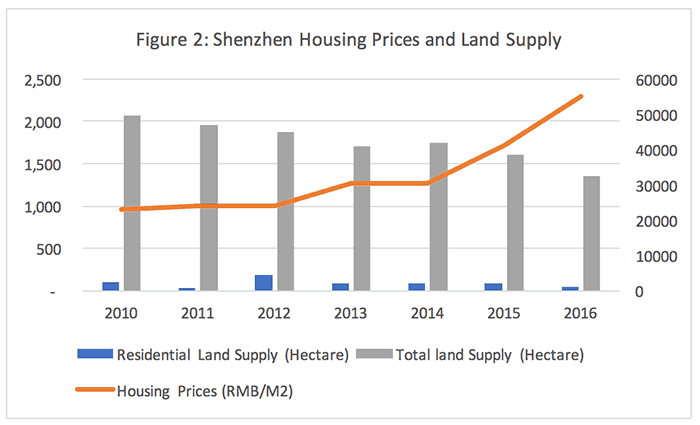

Figures 1 and 2 show the inverse relationship between new land supply and housing prices in Beijing and Shenzhen since 2010. The total land supply for urban use includes land made available for housing, infrastructure, green space, utilities and other purposes.

Local Governments Benefit From Housing Scarcity

In addition to central government goals for urban development, there are practical benefits to Chinese local governments from the ongoing imbalance between housing demand and land supply.

Sources: China Index Academy; Beijing Municipal Bureau of Land and Resources

Land leasing fees and related levies generally account for one third of revenues for local governments, with that figure rising as high as 60 percent in some cities. In 2016, total local government income from land transactions reached RMB 3.7 trillion.

With this reliance on real estate for revenue, local governments have incentives to create land scarcity and to synchronise any land sales with periods of peak developer demand.

Sources: China Index Academy, Shenzhen Bureau of Urban Planning, and Shenzhen Land and Resources Commission

As shown in figures 1 and 2, at the same time that housing prices in Beijing and Shenzhen have risen substantially over the past six years, the supply of new land sold has decreased slightly. And within the total land made available in Beijing and Shenzhen since 2010, only 18 percent and five percent was designated for development of commercial housing respectively.

Beijing Case Shows Opportunity for More Land Sales

Still, despite the conflicts of long range plans and local government incentives with China’s directives to increase land sales in major cities, there are already signs that the new rules may be having an impact.

At the start of 2017, Beijing planned to auction off just 610 hectares of new residential sites during this year. In mid-April, however, city authorities nearly doubled that target to 1200 hectares.

While Beijing’s move could indicate a new direction, other cities have yet to issue similar plans.

With China’s rapid development confronting the government with conflicting pressures to increase housing supply while maintaining local revenues, ensure social stability and protect the environment, this first attempt at regulating the housing market from the supply side faces significant challenges if it is to prove more effective at reining in housing prices than earlier demand side measures.

Lu Zhou is a doctoral candidate at Hong Kong University’s Department of Real Estate and Construction. This article was prepared as part of her ongoing research into China’s land policies and real estate development.

Leave a Reply